Why Kickstart? The Psychology of Hitting Pledge

After languishing in the pockets of massive studios for decades, the Internet’s disruptive influence has changed the modern video games industry in an incalculable number of ways. Digital distribution platforms such as Steam and GoG have blossomed in an extraordinary manner, bypassing the high street and allowing a range of developers to take their products directly to the public (Orr, 2016). New media, such as YouTube and Twitch, have largely replaced traditional content streams and social media’s influence has mushroomed (Staff, 2010). Thanks to this disruptive effect, even funding a video game has changed. Recently the team at Harmonix launched a crowdfunding initiative to bring the hugely successful Rock Band 4 to PC.

In a move that might strike casual observers as unusual, the devs behind the Rock Band franchise took to crowdfunding site Fig (https://www.fig.co/about) in an effort to raise $1.5 million needed to let keyboard warrior put together awesome riffs. Interestingly, Fig’s Rock Band campaign allowed backers to choose how they support the project. With the option to support as an investor and gain fairly lucrative returns, why would anybody choose to pledge to a campaign for physical rewards?

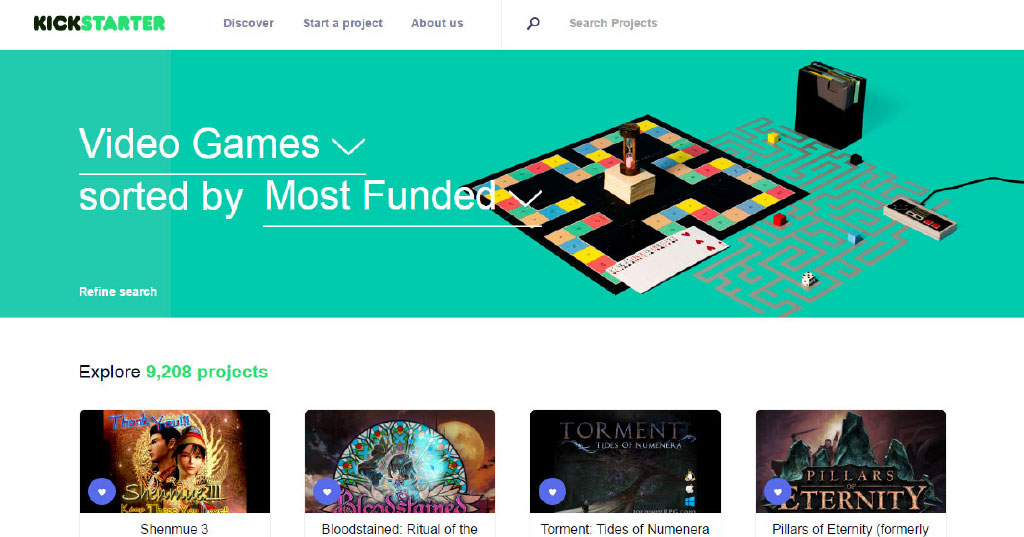

A result of increasing connectivity and the encroaching prevalence of the Internet, Kickstarter has fueled a step change in the way video games are funded and leads the charge for pledging. With over 10 million unique backers on Kickstarter alone, crowdfunding’s subversive influence reaches far beyond the realm of video games. From fancy footwear to Zack Danger’s infamous potato salad (Brown, 2014), crowdfunded projects can reward backers with a variety of physical goods, business equity, financial returns or the warm feeling that goodwill brings. In order to reach their goals, financial crowdfunding sites such as Crowdcube and Fig provide an option for more traditional investors to back a project with the promise of equity or monetary gains. Although equity and debt can provide an understandable enticement for financial investors, the psychology behind backing in Kickstarter is less clear. The motivation for Crowdcube’s investors more closely follows established financial theory without entirely discounting concepts such as choice, bias, and loss aversion. Kickstarter’s own model expressly forbids certain types of equity and debt funding, focusing on tangible rewards for its backers. This places Kickstarter in a unique position.

Backers of Kickstarter projects can expect anything from a simple acknowledgment to prototypes of the latest tech. This emphasis on tangible has parallels with more traditional consumer behaviour, yet pledging doesn’t necessarily guarantee prizes. An element of altruism exists on Kickstarter, yet it still maintains much of the inherent speculative structures of other crowdfunding platforms. Elements of behavioural finance, consumerism, and social psychology all crash together in a veritable mess of emotions, which influence our decision to finally click “Back This Project”.

Uncertainty is one of the decisive factors of any investment and the Kickstarter model has launched several high profile catastrophes that highlighted the risks in this particular area of the market . By the opening of 2015, the Zanos Kickstarter project appeared on Kickstarter and proceeded to take millions in pledges from a feverish torrent of backers. It promised a fully autonomous camera drone, capable of capturing action from any angle, completely independent of its subject.

It ended in unmitigated disaster. Rather than delivering the hi tech Go Pro of the future that had been demonstrated, the final production Zano turned out to be a listless contraption, scarcely numbering in the hundreds, that could barely fly and frequently crashed. Around $3.5 million of backers funds was lost, the company behind the Zano filed for liquidation, and the failure was damaging enough for Kickstarter to publish an investigation (Harris, 2016).

With studies citing figures of 1 in 11 kick-started projects failing to deliver, a fear of loss is natural. Khaneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory quantified the concept of loss aversion in the late 1970s (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). It explains human reaction to decision making, risk, and potential gains. When faced with risky decisions, such as the potential that a Kickstarter could collapse under an avalanche of backer expectation and an inability to properly budget, people tend to prefer avoiding losses above potential rewards. This is especially pertinent with Kickstarter projects which still fail to deliver more than 25% of projects on time, if at all (Pi, 2012) (Mollick, 2015).

Gambling on the possibility that a particular object of desire will be delivered seems, at best, illogical and counterintuitive to the consumer relationship that already exists between the public and games retailers. Generally, consumer behaviour can be described as processes involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use or dispose of products, services, ideas or experiences to satisfy needs and desires (Michael Solomon, 2012).

Kickstarter not only conforms to this description but could be considered as a monopoly, being the only point of sale for the unique rewards on show. Tangible rewards make Kickstarter unusual, allowing campaigns to leverage our own desire for consumption in the same way many retail outlets do. It is well established that retail consumers will make decisions based on their concept of self. This is influenced by a number of factors from self-affirmation, identification with a set of ideas, and affiliation, more commonly termed branding (Escalas, 2013) (Rani, 2014).

Personal affiliations, sub-cultures and the eventual buzz of a herd of fevered Internet fans can all arguably be influenced by one critical factor, social media. The power of social marketing is undeniable and an increasingly influential component of selling video games. Influence marketing is a firmly established technique that seeks to maximize the effective brand reach of a product by tapping into the myriad of social forces that a few, critical people can bring to bear (Henneberry, 2012). It uses their extended networks of contacts, high levels of engagement, personal investment, and association to create a brand awareness that can have a much deeper personal resonance than any commercial (Norman Booth, 2010).

Kickstarter is uniquely placed to observe the direct impact of social media on investment decisions. Kickstarter founders with more than one thousand Facebook friends have been shown to possess a staggering forty percent chance of meeting their goals, yet this falls into single figures when compared to more concentrated social networks (Pi, 2012). Statistically, successful Kickstarter campaigns appear to make use of social influence and the prevalence of social media on Kickstarter guides suggests that this has not gone unnoticed (Dawe, n.d.) (Agius, 2014). In short, if your friends are backing a Kickstarter, you are more likely to do so and Kickstarter knows it.

While social media busily coerces itself into a crescendo of excitement over any particular Kickstarter phenomenon, the chance to buy into a piece of the latest success story diminishes. Limited reward tiers, tight deadlines and funding goals place an undue emphasis on backers to pledge before time runs out. This fear can make Kickstarter rewards seem even more enticing and in many cases, helps to offset a natural fear of loss.

Despite the inherent, well publicized, risks of Kickstarting and natural human aversion to loss, the Kickstarter platform continues to go from strength to strength. Over $2.3 billion has been pledged to projects since Kickstarter’s initial launch and a constant stream of pledges continues to flow in (Statista.com, 2016). Unique and innovate games are developed with the help of crowdsourcing and innovate projects have changed the way we play video games. From the Oculus rift to the phenomenally successful Elite Dangerous, Kickstarter has brought us a multitude of projects we would never have otherwise seen.

Kickstarter is not as straightforward as other crowdfunding sites. Investment is not driven by financial returns and the decision to back a project is emotionally complex. Instead, Kickstarter relies on the pledger’s desire to invest in a cultural identity and the tangible rewards that come from it. In this respect, Kickstarter arguably sits somewhere between the curation platform of sites like Indiegogo and a traditional retail shopfront. In many ways, Kickstarter has become the riskiest and most rewarding purveyor of pre-orders.

Works Cited

- Agius, A. (2014, Septemaber 14). Content-Marketing Lessons From 4 Successful Kickstarter Campaigns. Retrieved from Entrepreneur.com: http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/237501

- Brown, Z. (2014, July). Potato Salad. Retrieved from Kickstarter:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/zackdangerbrown/potato-salad - Dawe, G. (n.d.). 100 Crowdfunding Influencers to Boost your Campaign. Retrieved from Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/100-crowdfunding-influencers-boost-your-campaign-giles-dawe

- Escalas, J. (2013). Self-Identity and Consumer Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, xv-xviii.

- Harris, M. (2016, Jan 16). How Zano Raised Millions on Kickstarter and Left Most Backers with Nothing. Retrieved from Medium.com:

https://medium.com/kickstarter/how-zano-raised-millions-on-kickstarter-and-left-backers-with-nearly-nothing-85c0abe4a6cb#.ph0uw9jaf - Henneberry, R. (2012, October 17). Industry Influencers. Retrieved from Social Media Examiner: http://www.socialmediaexaminer.com/industry-influencers/

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 263-292.

- Michael Solomon, R. R.-B. (2012). Consumer Behaviour. Pearson.

- Mollick, E. R. (2015). Delivery rates on Kickstarter. 24: December.

- Norman Booth, J. A. (2010). Mapping and Leveraging Influencers in Social Media to Shape Corporate Perceptions. Conference on Corporate Communication, (p. 16). Wroxton.

- Orr, E. (2016). Gaiscioch Magazine. Retrieved from Gaiscioch Magazine:

https://www.gaisciochmagazine.com/downloads/2016-8.pdf - Pi, J. (2012, July). The Untold Story Behind Kickstarter Stats. Retrieved from AppsBlogger:

http://www.appsblogger.com/behind-kickstarter-crowdfunding-stats/ - Rani, P. (2014). Factors influencing consumer behaviour. International Journal of Current Research and Academic Review, 52-61.

- Staff, P. R. (2010, May). New media, Old Media. Retrieved from Pew Research Centre:

http://www.journalism.org/2010/05/23/new-media-old-media/ - Statista.com. (2016). Total Kickstarterr Funding. Retrieved from Statista:

http://statista.com/statistics/310218/total-kickstarter-funding